The cat is out. And it has been replaced by a weasel. Yes, dear reader, you’ve entered the strange, paradoxical world of Schrödinger’s Weasel, a universe where words drift in a haze of semantic uncertainty, their meanings ambushed and reshaped by whoever gets there first.

Now, you may be asking yourself, “Haven’t we been here before?” Both yes and no. While the phenomenon of weasel words—terms that suck out all substance from a statement, leaving behind a polite but vacuous husk—has been dissected and discussed at length, there’s a new creature on the scene. Inspired by Essentially Contested Concepts, W.B. Gallie’s landmark essay from 1956, and John Kekes’ counterpoint in A Reconsideration, I find myself stepping further into the semantic thicket. I’ve long held a grudge against weasel words, but Schrödinger words are their sinister cousins, capable of quantum linguistic acrobatics.

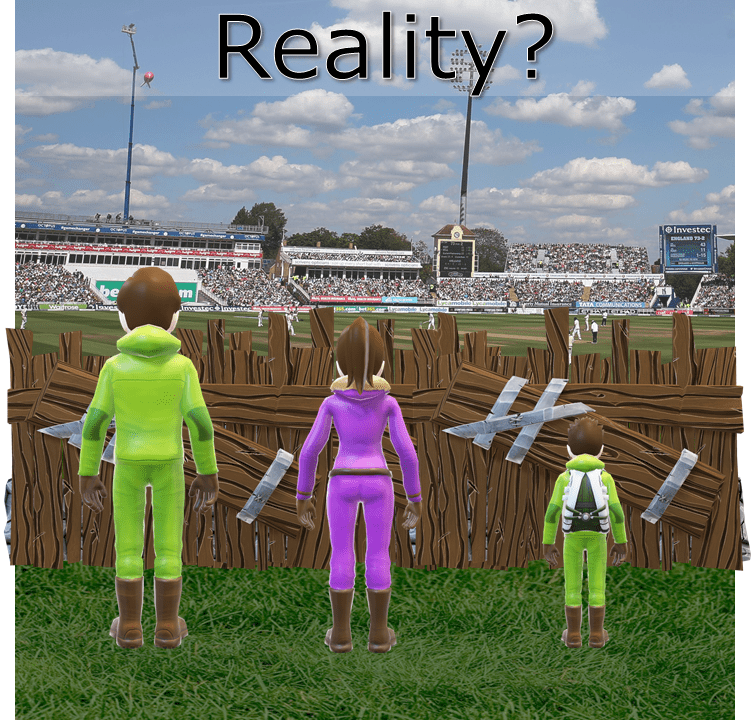

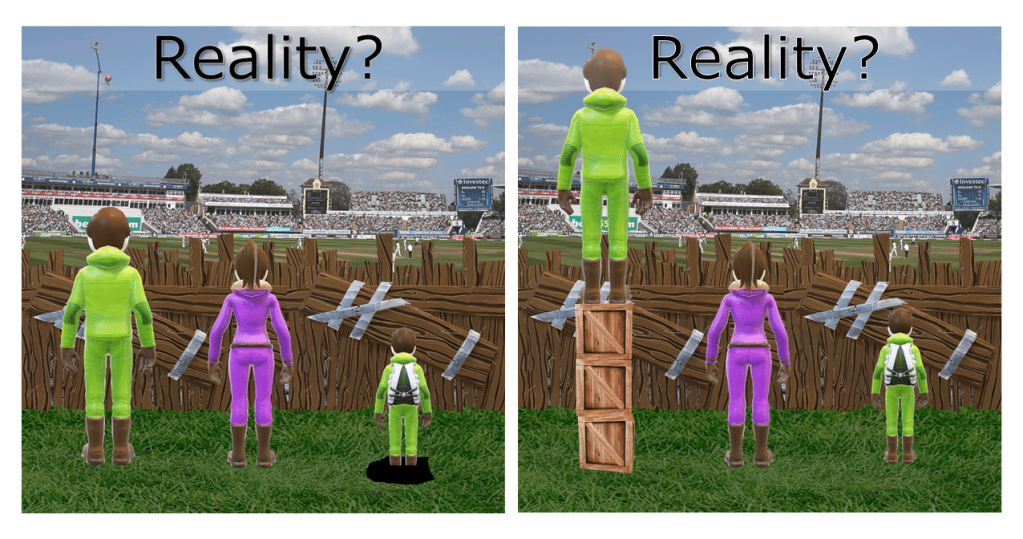

To understand Schrödinger words, we need to get cosy with a little quantum mechanics. Think of a Schrödinger word as a linguistic particle in a state of superposition. This isn’t the lazy drift of semantic shift—words that gently evolve over centuries, shaped by the ebb and flow of time and culture. No, these Schrödinger words behave more like quantum particles: observed from one angle, they mean one thing; from another, something completely different. They represent a political twilight zone, meanings oscillating between utopia and dystopia, refracted through the eye of the ideological beholder.

in the realm of Schrödinger’s Weasel, language becomes a battlefield where words are held hostage to polarising meanings

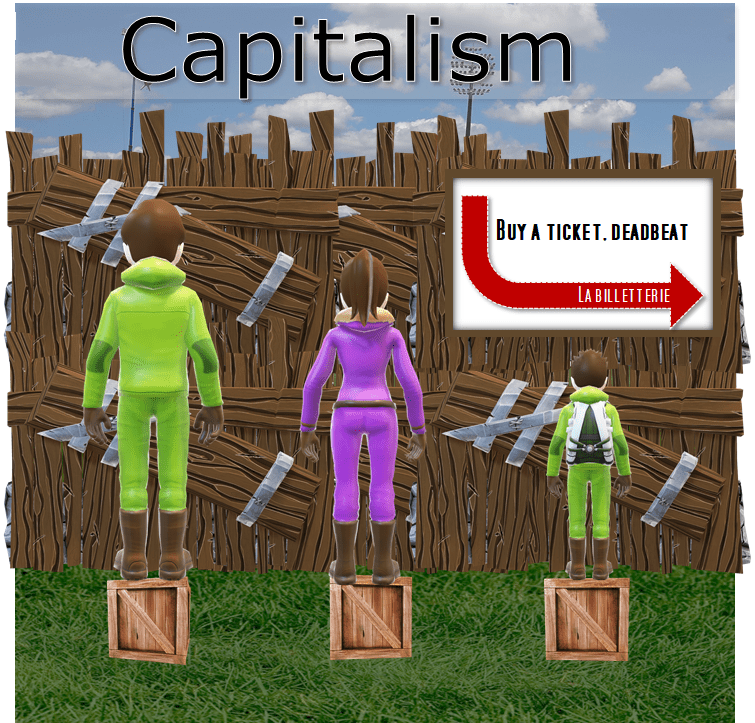

Take socialism, that darling of the Left and bugbear of the Right. To someone on the American political left, socialism conjures visions of Scandinavia’s welfare state, a society that looks after its people, where healthcare and education are universal rights. But say socialism to someone on the right, and you might find yourself facing the ghost of Stalin’s Soviet Union – gulags, oppression, the Cold War spectre of forced equality. The same word, but two worlds apart. This isn’t simply a “difference of opinion.” This is linguistic quantum mechanics at work, where meaning is determined by the observer’s political perspective. In fact, in the case of Schrödinger words, the observer’s interpretation not only reveals meaning but can be weaponised to change it, on the fly, at a whim.

What, then, is a Schrödinger word? Unlike the classic weasel words, which diffuse responsibility (“some say”), Schrödinger words don’t just obscure meaning; they provoke it and elicit strong, polarised responses by oscillating between two definitions. They are meaning-shifters, intentionally wielded to provoke division and rally allegiances. They serve as shibboleths and dog whistles, coded signals that change as they cross ideological boundaries. They are the linguistic weasels, alive and dead in the political discourse, simultaneously uniting and dividing depending on the audience. These words are spoken with the ease of conventional language, yet they pack a quantum punch, morphing as they interact with the listener’s biases.

Consider woke, a term once employed as a rallying cry for awareness and social justice. Today, its mere utterance can either sanctify or vilify. The ideological Left may still use it with pride – a banner for the politically conscious. But to the Right, woke has become a pejorative, shorthand for zealous moralism and unwelcome change. In the blink of an eye, woke transforms from a badge of honour into an accusation, from an earnest call to action into a threat. Its meaning is suspended in ambiguity, but that ambiguity is precisely what makes it effective. No one can agree on what woke “really means” anymore, and that’s the point. It’s not merely contested; it’s an arena, a battlefield.

What of fascism, another Schrödinger word, swirling in a storm of contradictory meanings? For some, it’s the historical spectre of jackboots, propaganda, and the violence of Hitler and Mussolini. For others, it’s a term of derision for any political stance perceived as overly authoritarian. It can mean militarism and far-right nationalism, or it can simply signify any overreach of government control, depending on who’s shouting. The Left may wield it to paint images of encroaching authoritarianism; the Right might invoke it to point fingers at the “thought police” of progressive culture. Fascism, once specific and terrifying, has been pulled and stretched into meaninglessness, weaponised to instil fear in diametrically opposed directions.

Schrödinger’s Weasel, then, is more than a linguistic curiosity. It’s a testament to the insidious power of language in shaping – and distorting – reality. By existing in a state of perpetual ambiguity, Schrödinger words serve as instruments of division. They are linguistic magic tricks, elusive yet profoundly effective, capturing not just the breadth of ideological differences but the emotional intensity they provoke. They are not innocent or neutral; they are ideological tools, words stripped of stable meaning and retooled for a moment’s political convenience.

Gallie’s notion of essentially contested concepts allows us to see how words like justice, democracy, and freedom have long been arenas of ideological struggle, their definitions tugged by factions seeking to claim the moral high ground. But Schrödinger words go further – they’re not just arenas but shifting shadows, their meanings purposefully hazy, with no intention of arriving at a universally accepted definition. They are not debated in the spirit of mutual understanding but deployed to deepen the rift between competing sides. Kekes’ critique in A Reconsideration touches on this, suggesting that the contestation of terms like freedom and democracy still strives for some level of shared understanding. Schrödinger words, by contrast, live in the gap, forever contested, forever unresolved, their ambiguity cherished rather than lamented.

Ultimately, in the realm of Schrödinger’s Weasel, language becomes a battlefield where words are held hostage to polarising meanings. Their superposition is deliberate, their ambiguity cultivated. In this brave new lexicon, we see language not as a bridge of understanding but as a weapon of mass disinformation – a trick with all the precision of quantum mechanics but none of the accountability. Whether this ambiguity will one day collapse into meaning, as particles do when measured, remains uncertain. Until then, Schrödinger’s Weasel prowls, its meaning indeterminate, serving whichever agenda is quickest to claim it.