I’ve spend some hours cobbling together another video that I labelled Free Will Scepticism: Would-Be Agency & Luck. I’ve embedded it here. The script is below.

Human agency does not exist. Free will is an illusion. Like the appearance that the sun rises in the east and sets and the west, we only appear to have free will.

There are some nuances and varying degrees of this belief, but if one believes in the scientific notion of cause and effect, that every effect is the result of a prior cause of causes, one inevitably ends up in this camp.

[REDACTED]

Without going into details because the focus of this segment is on luck, I’d still like to set the stage for the uninitiated.

Regarding the universe, we recognise a relationship between cause and effect. If we rewind to follow this logic back to the beginning of time and started again, we’d end up in exactly the same place. This is known as deterministic. What happens next is determined by what happened before.

And this is not just a scientific view. Those who believe that God caused the universe can arrive at this same place.

Owing to advancements in scientific thought, most philosophers today do not believe that the world is deterministic, per se. Given theories of quantum mechanics and probabilistic outcomes, they believe in so-called natural physical laws, but probability is also part of this model.

One may strike a billiard ball with a cue stick to cause it to strike another ball, knocking it into a pocket. In our knowledge of the universe, this is unsurprising. If one set this up mechanically, leaving no room for variation, we could run this scenario over and over again forever, and the ball would go into the pocket every time. The outcome is established by the laws of physics.

Actually, this is just another illusion. The laws of physics cause nothing. They are just a way of describing how things unfold in our universe. But just like saying that the sun rises in the east, we can employ idiomatic language and people know what we mean.

This was an illustration of determinism. Indeterminism accepts these same laws, but it adds an element of probability. In our mechanised billiards example, perhaps a ball is randomly rolled across the table in such a way that it might interfere with the path of the balls.

If the random ball does not interfere with the path, its presence is irrelevant. If it does interfere, there are a few different outcomes.

One, it knocks a ball off course, so the final ball does not go into the pocket.

Two, its path is such that although it collides with a ball, this event does not interfere with the final ball ending up in the pocket, so a person fixated on the pocket might not notice anything more than a slight delay in the occurrence of the event.

The second scenario depicts indeterminism.

In both scenarios, the ball expected to go into the pocket is the would-be agent. As illustrated, the ball itself has no agency. None of them does. Its fate, to borrow a term steeped in metaphysics, is entirely subject to the actions before it. And then there’s chance, so let’s continue.

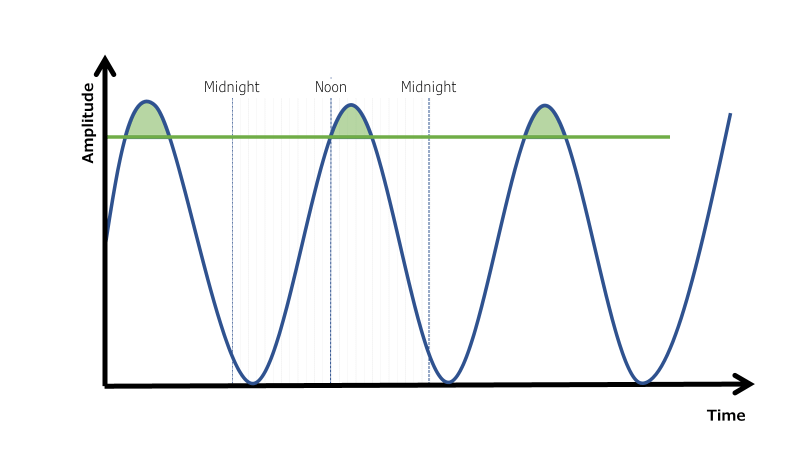

Humans are ostensibly automatons, subject to their genetic and environmental programming with no degree of free will. Let’s say that in a given context each person can be described by a certain wave function. For the sake of simplicity, let’s just pretend that it can be represented by a sine wave. As with any waveform, we can illustrate it by plotting it on a 2-dimensional plane, having amplitude on the Y-axis and time on the X-axis. Let’s consider this to be analogous to a person’s biorhythm, and let’s further consider that this represents the would-be agent’s mood or propensity to behave a certain way.

Practically, there might be more functions, so let’s just say that this is the average of all of these other functions—perhaps the other functions being how much rest was had the night before, when and what the last meal was, traffic encountered on the way to work, and any number of other personal considerations.

For any stable wave, we can plot the period from peak to peak or trough to trough. Let’s use trough to trough to represent a period of a day but from 2:30 am to 2:30 am rather than from midnight to midnight. This is one complete cycle. The offset is just to more easily facilitate the scenario.

Given this frame, we’ll put noon in the centre between the midnights as expected.

For the purposes of illustration, we’ll draw a horizontal line to represent a threshold depicting a change in disposition. We’ll use this later.

Finally, let’s show time increments by hour, so we now see 24 hours in a day. And we can see that at noon the wave peak rises above the threshold and falls below the threshold again at 5 pm.

Let’s presume that this wave function represents that of a criminal trial judge. There is support for this notion as published in Daniel Kahneman’s 2021 book, Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, wherein he notes that trial judges are almost as predictable as a watch, that their sentences are more correlated with time of day and the aforementioned factors than anything related to law—save for the laws of time, I suppose.

Remembering that—like all people—this judge is an automaton. Let’s build some character—rather characteristics. Judge Judy believes that people are fundamentally bad and not to be trusted. She believes that they have free will and are accountable for their actions, though she does also allow for extenuating circumstances when considering sentencing, the usual suspects—bad childhood, chemical dependency, and whatnot. People who believe more strongly in free will are more likely to believe in harsher punishment. Judy is no exception.

Using this function as a guide, above the threshold represents her propensity for leniency. She tends to take lunch regularly before noon and is more lenient for a period after lunch. Data show that this effect is closer to a couple of hours after the midday meal, but we are simplifying.

Zooming in, let’s just consider a single day in the life of another would-be agent who as it happens will be interacting with our Judge Judy. I’ll take this opportunity to introduce the work of Neil Levy.

Neil is Head of Neuroethics at the Florey Neuroscience Institutes and Director of Research at the Oxford Centre for Neuroethics.

He is the author of Hard Luck, five previous books, and many articles, on a wide range of topics including applied ethics, free will and moral responsibility, philosophical psychology, and philosophy of mind.

Levy’s book promotes the concept that even if we allow for human agency, much of this supposed agency is undermined by luck. This will not only become evident in the scenario we are working through, but as a human, you may come upon a decision-point, where probability and luck come into play. You have no control over what ideas pop into your head—or don’t—and in what order. The choice you ultimately make is limited to what these ideas are and how they do or don’t manifest. Without going too far astray, perhaps you’ve constructed a false dichotomy.

Perhaps you are confronted by a stranger in a dark alley. You observe that it’s a dead end. The stranger, asking for money, approaches you in a manner you interpret as menacing. As he reaches into his coat, you pull out your concealed weapon and fatally shoot him.

He was unarmed. No longer in panic, you realise that you are not in a dead-end alley.

When the police arrive, they inform you that the person you killed is known` by law enforcement and social services, who have been keeping an eye on him because he had limited cognitive capacity and resided in a group home. Not only was he not armed, but the detective on the scene noted that what he was reaching for were pens with inspirational inscriptions that he routinely sold to earn money.

Whilst you may not have been able to determine that he was otherwise harmless, it was your ‘luck’—bad luck—that you didn’t happen to see that you were never cornered in the first place.

Nevertheless, you are arrested.

In another scenario, perhaps there are two judges. Judge Judy and Justice Joe. As it happens, Justice Joe has a cycle reverse to Judy. Where Judy’s mood is better after lunch, Joe is fasting, and his mood gets worse. This means that your fate now is not only tied to the time of day but it’s also linked to the luck of which judge will hand down your sentence.

If you are a strict determinist, then the “universe” has already determined which judge will sentence you.

If you are an indeterminist, then the universe will flip a coin. And the probability of a case running long or short might determine the time of day.

In the end, as are you, the judges are slaves to their programming, and any alteration of inputs will just be processed through whatever they’ve become until that point. They have no more free will than you do. The die has already been cast.

Do you believe you have free will? If so, why. Are you a determinist or an indeterminist? Or are you a compatibilist who believes that free will and determinism can coexist in the same universe?

Comment below or on YouTube.