Generative AI (Gen AI) might seem like a technological marvel, a digital genie conjuring ideas, images, and even conversations on demand. It’s a brilliant tool, no question; I use it daily for images, videos, and writing, and overall, I’d call it a net benefit. But let’s not overlook the cracks in the gilded tech veneer. Gen AI comes with its fair share of downsides—some of which are as gaping as the Mariana Trench.

First, a quick word on preferences. Depending on the task at hand, I tend to use OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, and Perplexity.ai, with a particular focus on Google’s NotebookLM. For this piece, I’ll use NotebookLM as my example, but the broader discussion holds for all Gen AI tools.

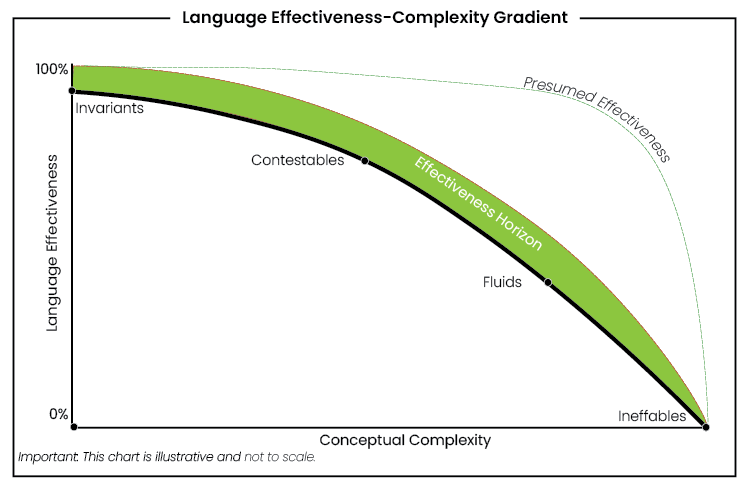

Now, as someone who’s knee-deep in the intricacies of language, I’ve been drafting a piece supporting my Language Insufficiency Hypothesis. My hypothesis is simple enough: language, for all its wonders, is woefully insufficient when it comes to conveying the full spectrum of human experience, especially as concepts become abstract. Gen AI has become an informal editor and critic in my drafting process. I feed in bits and pieces, throw work-in-progress into the digital grinder, and sift through the feedback. Often, it’s insightful; occasionally, it’s a mess. And herein lies the rub: with Gen AI, one has to play babysitter, comparing outputs and sending responses back and forth among the tools to spot and correct errors. Like cross-examining witnesses, if you will.

But NotebookLM is different from the others. While it’s designed for summarisation, it goes beyond by offering podcasts—yes, podcasts—where it generates dialogue between two AI voices. You have some control over the direction of the conversation, but ultimately, the way it handles and interprets your input depends on internal mechanics you don’t see or control.

So, I put NotebookLM to the test with a draft of my paper on the Language Effectiveness-Complexity Gradient. The model I’m developing posits that as terminology becomes more complex, it also becomes less effective. Some concepts, the so-called “ineffables,” are essentially untranslatable, or at best, communicatively inefficient. Think of describing the precise shade of blue you can see but can’t quite capture in words—or, to borrow from Thomas Nagel, explaining “what it’s like to be a bat.” NotebookLM managed to grasp my model with impressive accuracy—up to a point. It scored between 80 to 100 percent on interpretations, but when it veered off course, it did so spectacularly.

For instance, in one podcast rendition, the AI’s male voice attempted to give an example of an “immediate,” a term I use to refer to raw, preverbal sensations like hunger or pain. Instead, it plucked an example from the ineffable end of the gradient, discussing the experience of qualia. The slip was obvious to me, but imagine this wasn’t my own work. Imagine instead a student relying on AI to summarise a complex text for a paper or exam. The error might go unnoticed, resulting in a flawed interpretation.

The risks don’t end there. Gen AI’s penchant for generating “creative” content is notorious among coders. Ask ChatGPT to whip up some code, and it’ll eagerly oblige—sometimes with disastrous results. I’ve used it for macros and simple snippets, and for the most part, it delivers, but I’m no coder. For professionals, it can and has produced buggy or invalid code, leading to all sorts of confusion and frustration.

Ultimately, these tools demand vigilance. If you’re asking Gen AI to help with homework, you might find it’s as reliable as a well-meaning but utterly clueless parent who’s keen to help but hasn’t cracked a textbook in years. And as we’ve all learned by now, well-meaning intentions rarely translate to accurate outcomes.

The takeaway? Use Gen AI as an aid, not a crutch. It’s a handy tool, but the moment you let it think for you, you’re on shaky ground. Keep it at arm’s length; like any assistant, it can take you far—just don’t ask it to lead.