This is a continued reflection of the ramifications of yesterday’s post.

There is a growing tendency to describe certain moral conflicts as educational failures: If only people were shown the right perspective. If only they listened. If only they learned to see differently.

This language is most visible in discussions of objectification. Some men are told that what they perceive, feel, or notice is something that can be unlearned through dialogue. That with sufficient moral instruction, a perceptual orientation can be rewired into a different one. The problem is not that this ambition is moral. The problem is that it is architecturally incoherent.

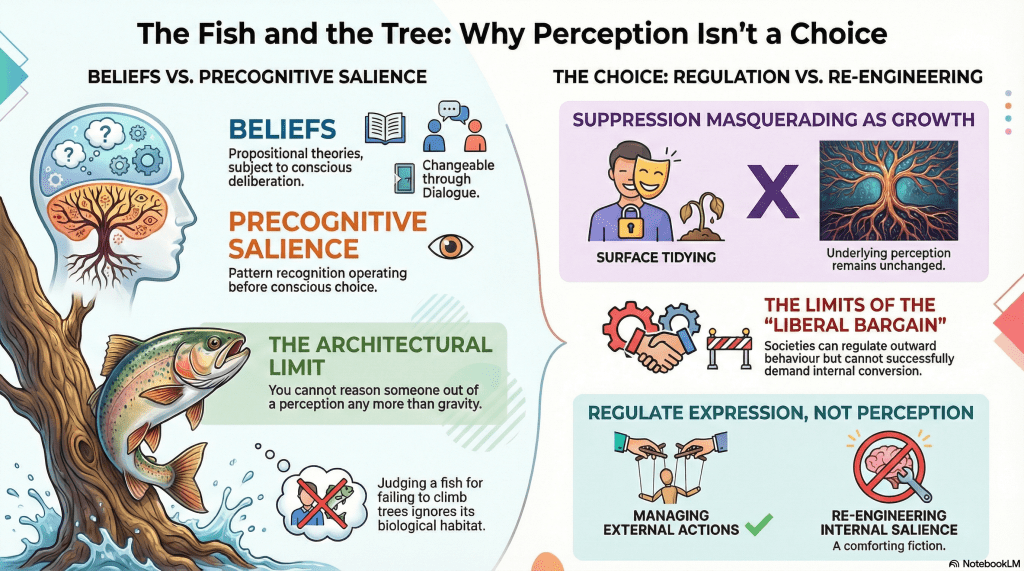

The category mistake at the centre

Objectification is routinely treated as if it were a belief. A proposition. A theory about women that can be corrected with better arguments.

But much of what is being targeted is not propositional at all. It is precognitive salience. Attentional bias. Pattern recognition that operates before language, before justification, before conscious choice. You cannot reason someone out of a perception any more than you can lecture the vestibular system into ignoring gravity.

This is not a defence of behaviour. It is a refusal to confuse perception with endorsement. When we mistake a precognitive state for a belief, we end up conducting moral seminars aimed at the wrong organ.

What education quietly becomes

Once this mistake is made, the rest follows with grim reliability.

If the orientation persists after instruction, it is no longer treated as structural. It is treated as obstinacy. The individual is said not merely to have a problematic perception but to be refusing growth.

At this point, moral education slides into something else entirely. Compliance is redescribed as transformation. Suppression is redescribed as insight. Silence is redescribed as progress.

The person learns to inhibit expression, to monitor language, to filter behaviour. None of this touches the underlying salience structure. But the culture congratulates itself anyway, because the surface has been tidied. This is how behavioural containment comes to masquerade as moral reform.

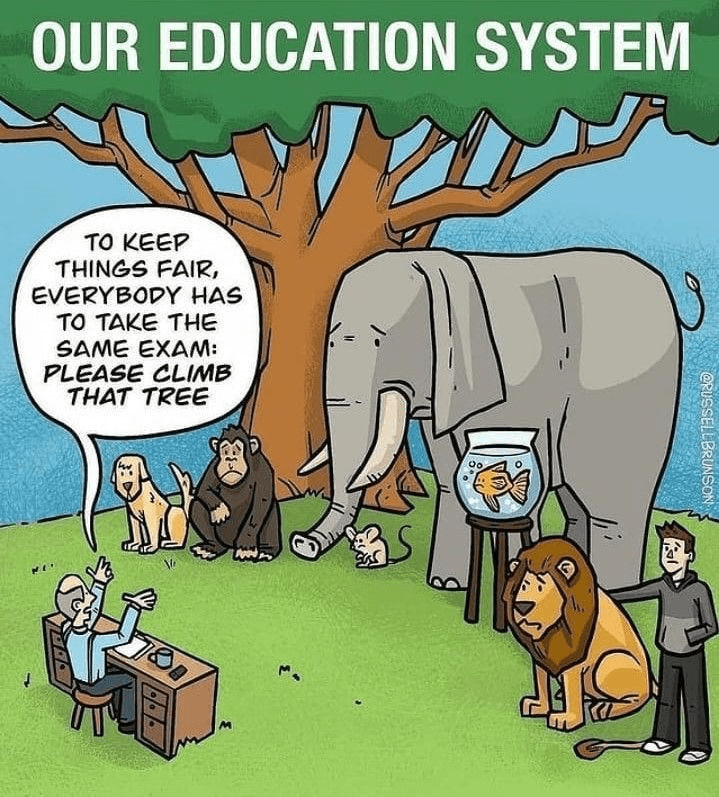

The fish and the trees

The fish analogy is not flippant. It is diagnostic. Telling a fish it must climb trees is not an invitation to growth. It is a refusal to acknowledge habitat. When the fish fails, the failure is moralised.

- ‘You could do this if you tried.’

- ‘Others have managed.’

- ‘Your resistance is the problem.’

The water is never named. Only the inadequacy of the swimmer.

Likewise, telling someone that a precognitive orientation can be dialogically dismantled assumes a plasticity that does not exist. When it fails, the failure is framed as an ethical defect rather than an architectural limit.

A topical case study

Rather than think in abstractions, let’s use a culturally-relevant example – at least through a relatively recent US frame – objectifying women. This has been a topic since at least the 1970s, and it remains in the cultural consciousness.

Some men have been accused of objectifying women. They are told this is wrong and asked to change their perspectives. But what’s really happening here?

These people are being asked to suppress the expression of a precognitive state. In Haidt’s parlance, they are being chastised for not controlling their elephant.

No amount of dialogue will rewire this faculty. This is akin to judging the fish for not climbing a tree and adopting an arboreal lifestyle.

I am not saying that all men are wired like this, nor am I saying that some men cannot control their baser impulses, but I am saying that asking a person not to express something does not thwart the impulse. In fact, it may make them also feel guilty for this instinct.

Why this becomes culturally unstable

A culture can regulate behaviour without demanding internal conversion. That is the old liberal bargain. You may think what you think; you will act within bounds.

What it cannot do indefinitely is promise inner transformation it cannot deliver, while punishing those who fail to achieve it. That produces exhaustion. It produces resentment. It produces a constant background hum of self-surveillance.

Worse, it moralises involuntary cognition. Not what you do, but what you notice. Not action, but salience. Not harm, but perception. Once that line is crossed, the scope of moral suspicion expands without limit.

The choice we avoid naming

The dilemma is not whether objectifying behaviour should be constrained. It should.

The dilemma is whether we will admit the difference between:

- regulating expression, and

- re-engineering perception

One is possible. The other is a comforting fiction. Pretending otherwise allows us to speak the language of enlightenment while practising the mechanics of discipline. It lets us call suppression ‘growth’ and exhaustion ‘progress’. The honest position is less flattering.

Some orientations cannot be taught away. They can be managed, constrained, and socially bounded. Demanding more than that is not moral ambition. It is ontological impatience.

You can’t teach a fish to stop being wet. You can decide which waters it is allowed to swim in.

In the end, the point is that it isn’t a matter of knowing; it’s a matter of feeling – something much deeper.