I’ve read about 85 per cent of James by Percival Everett. I recommend it. On the surface, it is simply a very good story set in the narrative universe of Mark Twain’s Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer. I will avoid spoilers as best I can.

The novel is set in the antebellum American South. James and the others move through Missouri, a state that openly supported slavery, and at one point into Illinois, a state that officially opposed it but quietly failed to live up to its own rhetoric. Illinois, it turns out, is no safe haven. Ideology and practice, as ever, are on speaking terms only when it suits them.

This is not a book review. I may write one later for my Ridley Park site once I’ve finished the book. What interests me here are two philosophical tensions Everett stages with remarkable economy.

There are two characters who are Black but able to pass as white. One of them feels profound guilt about this. He was raised as a slave, escaped, and knows exactly what it means to be treated as Black because he has lived it. Passing feels like theft. Survival, perhaps, but theft all the same.

The other is more unsettled. He was raised as a white man and only later discovers that he is not, as the language goes, “pure-bred”. This revelation leaves him suspended between identities. Should he now accept a Black identity he has never inhabited, or continue to pass quietly, benefitting from a system that would destroy him if it knew?

James offers him advice that is as brutal as it is lucid:

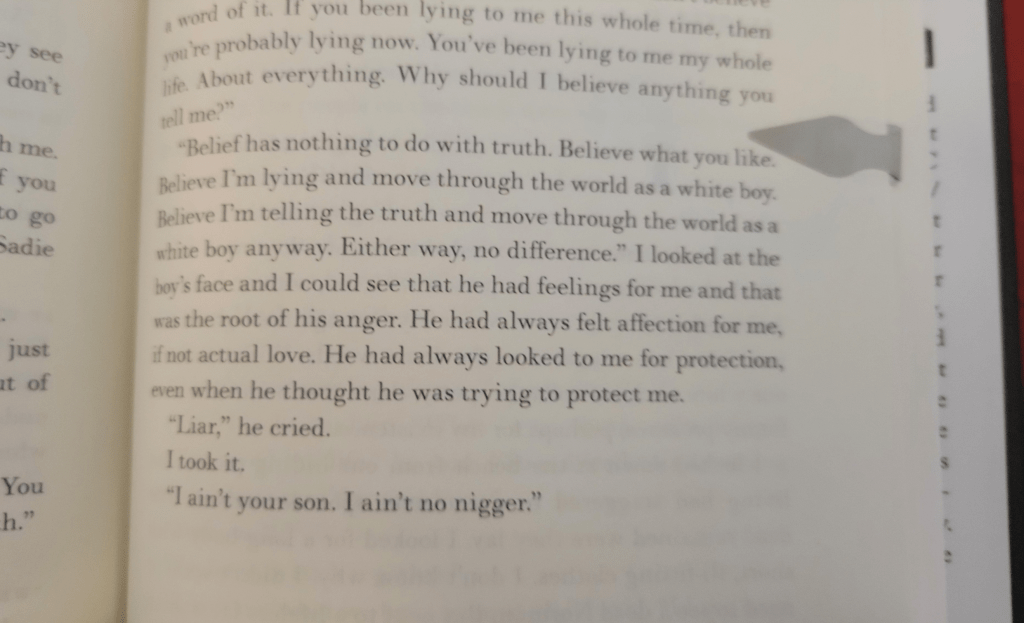

“Belief has nothing to do with truth. Believe what you like. Believe I’m lying and move through the world as a white boy. Believe I’m telling the truth and move through the world as a white boy anyway. Either way, no difference.”

This is the philosophical nerve of the book.

Truth, Everett suggests, is indifferent to belief. Belief does not mediate justice. It does not reorganise power. It does not rewire how the world responds to your body. What matters is not what is true, nor even what is believed to be true, but how one is seen.

The world does not respond to essences. It responds to appearances.

Identity here is not an inner fact waiting to be acknowledged; it is a surface phenomenon enforced by institutions, habits, and violence. The truth can be known, spoken, even proven, and still change nothing. The social machine runs on perception, not ontology.

In James, Everett is not offering moral comfort. He is stripping away a modernist fantasy: that truth, once revealed, obliges the world to behave differently. It doesn’t. The world only cares what you look like while moving through it.

Truth, it turns out, is perfectly compatible with injustice.