Apologies in advance for another business-oriented post, but it ties in well with the latest McGilchrist content. Simon Sinek is the presenter, and he asks how the Navy pick the members of Seal Team Six—as he says, “the best of the best of the best of the best,” which happens to align with the way my toddler might tell me how very, very, very, very much she likes something.

Simon is an adept communicator with a high woo factor, but this isn’t about him. I’ve cued this video to a place where Simon illustrates the assessment mindset employed to separate the wheat from the chaff in the minds of the Navy command. I’ve effectively recreated the chart Simon draws, and I use it as a reference.

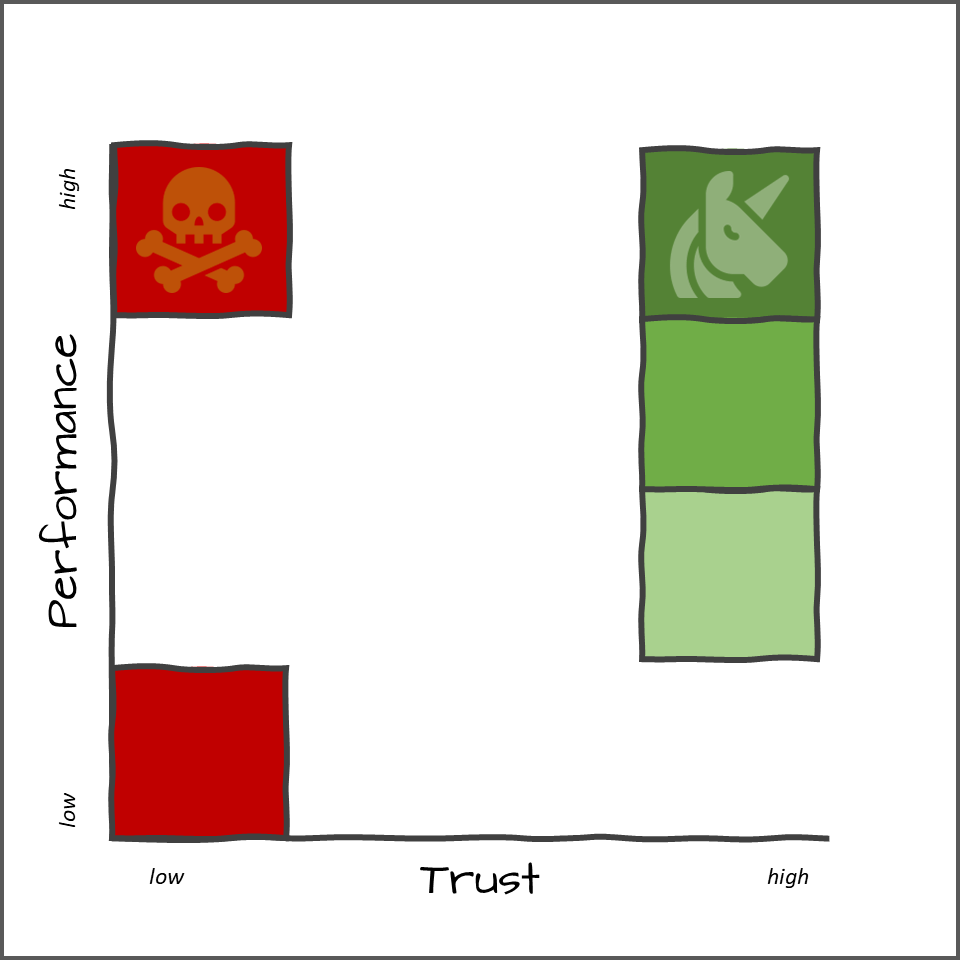

Performance is on the Y-axis and Trust is on the X-axis. Effectively, they assess competency on and off the battlefield, respectively. He describes Performance as capturing “Do I trust you with my life?” and Trust as “Do I trust you with my money and my wife?” Perhaps he’s reflecting the sentiment of the generation managing the Seals. Not judging.

His point is that no one wants an untrustworthy low-performer (bottom left) and everyone wants a trustworthy high-performer (top right). He goes on to say that high-performing, low-trust members are toxic to the team. The team is better off with a relatively moderate performer that is otherwise trustworthy. I suppose the rest is a wash.

Performance is typical left-hemisphere fare: how much, how many, how fast, and so on. Companies have a million and one ways to measure performance.

Trust is a resident of the right hemisphere. This is an intuition and can’t be measured.

As Simon points out, even without explicit metrics, if you ask each team member who’s the highest performer, they’ll all point to the same person. Correspondingly, if you ask who’s the most trustworthy, they’ll all point to the same person as well. I can’t say that I trust this judgment, and thankfully, they do document whatever performance measures they have determined are appropriate. This option is not available for trust, so they have to rely on intuition. I don’t know if they also rely on consensus. I will grant that if all of the members do point to the same person as having the highest level of trust–presuming some performance threshold has been met–and the goal is to find a leader for that team, this person would make a fine leading candidate. If this person happened to be the highest performer then great, but being the best leader doesn’t require being the highest performer.

A sports coach doesn’t even need to excel at the sport s/he is leading. Their function is to motivate and inspire the team. Of course, in the case of the seals, I’m presuming this role is more of a player-manager. Still, the cohesion factor should be taken into account.

Trust is a heuristic that can’t be measured, and it’s fairly simple to find examples of people who appeared to be trustworthy but turned out not to be. It’s also conceivable that a trustworthy person may be misunderstood and perceived as trustworthy.

My question relates to the object of trust. When I think of police officers in the United States, I think that their trust is in each other, but at the expense of society. So they will generally protect each other even when they are morally and legally in the wrong. This is not the trust we want to foster for the public good. But since in my opinion policing is not about the public good but rather maintaining the status quo power structure, this is not a problem for their hiring managers.