Words have inherent meaning. Unlike the common wisdom, the meaning of words is not arbitrary. Embedded in them is a relationship to the real-world experience. Or so Iain McGilchrist would have you believe. I’m afraid, I am not ready to buy into this assertion.

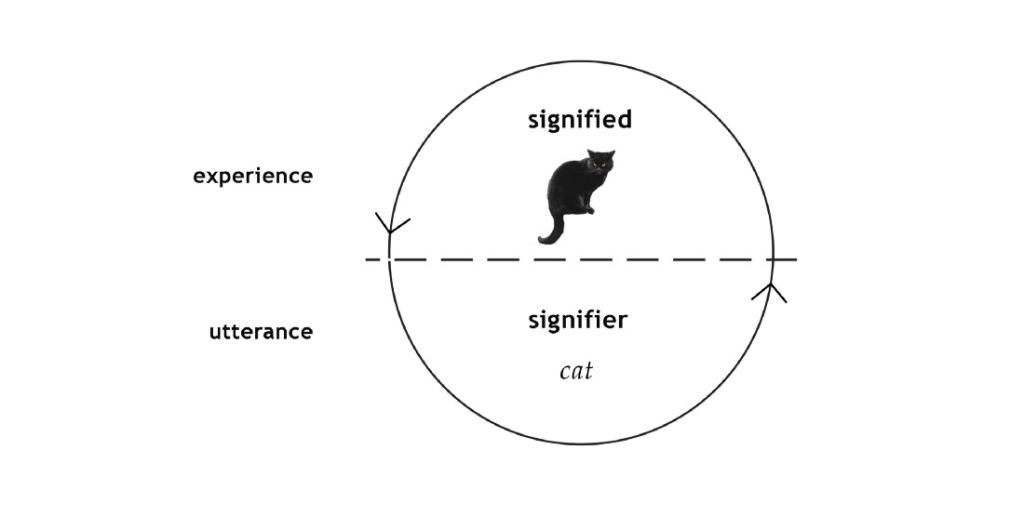

In chapter three of The Master and His Emissary, McGilchrist informs the reader that Ferdinand de Saussure is wrong in articulating there are referents and references, symbols and symbolised, signifiers and signified, or in his native French, signifiant and signifié. This falls into the realm of symbols and symbolic language, the domain of the left hemisphere. If you’ve been following along with my summary of The Matter with Things, you’ll know that this is not a flatter. To call someone left-brained is to accuse them of being out of touch and wrong. They are narrow, myopic thinkers, always trying to reduce the world to maps and symbols, which is of course precisely what Saussure does.

Let’s turn back the clock to July 2022. It was about then I had been introduced to the work of McGilchrist. In Intuition Showdown, I wrote about my reluctance to engage with it. I could sense that psychology was going to stake a claim to have the real perspective on reality. I wasn’t wrong. And it gets worse.

Effectively, McGilchrist establishes the left hemisphere as the village idiot. It’s a useful idiot and a halfway reliable emissary, but it’s closer to Lenny than George or a less fortunate Forrest Gump. And now he tosses Saussure into the pile. Here’s the kicker: To defend someone who’s been given this scarlet letter, is to be relegated to this category by association. Your defence is an admission that you, too are a left hemisphere dolt.

Be that as it may, I am standing in solidarity with Saussure on this one. I should probably wait until I’ve read chapter five, as Iain informs, there is more on the topic of language to come. For one reason, McGilchrist’s assertion rests on a sketchy study. To be fair, I’ve not delved deeply into the topic nor have I read the original study or evaluated the methodology, but here is how Iain portrays it.

There is, however, plenty of evidence that the sounds of words are not arbitrary, but evocative, in a synaesthetic way, of the experience of the things they refer to. As has been repeatedly demonstrated, those with absolutely no knowledge of a language can nonetheless correctly guess which word – which of these supposedly arbitrary signs – goes with which object, in what has become known as the ‘kiki/bouba’ effect (‘kiki’ suggesting a spiky-shaped object, where ‘bouba’ suggests a softly rounded object). [ref] However much language may protest to the contrary, its origins lie in the body as a whole. And the existence of a close relationship between bodily gesture and verbal syntax implies that it is not just concrete nouns, the ‘thing-words’, but even the most apparently formal and logical elements of language, that originate in the body and emotion. The deep structure of syntax is founded on the fixed sequences of limb movement in running creatures.111 This supports evidence that I will examine in Chapter 5 that the very structures and content of thought itself exist in the body prior to their utterance in language.

He cites Wittgenstein as well, who wrote about the disconnexion between language and the real world.

Without becoming mired in the details of this kiki/bouba effect study, as a former statistician donning my statistician hat, I find this study to be suspect. Although there appears to be a general tendency for neurotypical people to identify the spiky shape as kiki and the curvy shape as bouba, it’s quite a stretch to then conclude that all symbolic language has a similar basis. Although most (but not all) cultures conform to pairing these shapes with these nonce words generally, it would be more meaningful to extend this to at least a dozen shapes to see if this persists. Even then, this doesn’t connect this concept to common vocabulary words, whether spoken or written.

I do believe that conceptual thought precedes articulated language. I just don’t believe that these conceptual notions materially shape the words chosen to represent them. Proto-Indo-European theories aside, there is too much language diversity to account for this progenerative hypothesis.

I may return convinced after reading chapter five, but I somehow doubt it unless there is a lot more empirical support. For now, this is one of several disagreements I have with McGilchrist, though I probably agree with ninety-odd per cent of his work. I’ll keep reading The Master and His Emissary as well as The Matter with Things. I recommend that you do as well.

Seeking an image to illustrate Saussure’s signified and signifier, I happened upon a nice summary of semiotics. I also found this extension of Saussure by Roland Barthes. If you visit the site, you’ll also discover how Charles Sanders Pierce envisaged it,

My [admittedly limited] experience has been that authors who diss “left-brained” and “binary” thinking also use a lot of non sequiturs in their writing, and make loosely supported or unsupported assertions. Go figure.

LikeLike