The paper is now available on Zenodo.

I’ve been wittering on about social ontological positions and legibility for a few months now. I’ve been writing a book and several essays, but this is the first to be published. In it, I not only counter Ranalli – not personally; his adopted belief – I also counter Thomas Sowell, George Lakoff, Jonathan Haidt, Kurt Gray, and Joshua Green. (Counter might be a little harsh; I agree with their conclusions, but I remain on the path they stray from.)

There is a strange faith circulating in contemporary culture: the belief that disagreement persists because someone, somewhere, hasn’t been taught how to think properly.

The prescription is always the same. Teach critical thinking. Encourage openness. Expose people to alternatives. If they would only slow down, examine the evidence, and reflect honestly, the right conclusions would present themselves.

When this doesn’t work, the explanation is equally ready to hand. The person must be biased. Indoctrinated. Captured by ideology. Reason-resistant.

What’s rarely considered is a simpler possibility: nothing has gone wrong.

Most of our public arguments assume that we are all operating inside the same conceptual space, disagreeing only about how to populate it. We imagine a shared menu of reasons, facts, and values, from which different people select poorly. On that picture, better reasoning should fix things.

But what if the menu itself isn’t shared?

What if what counts as a ‘reason’, what qualifies as ‘evidence’, or what even registers as a meaningful alternative is already structured differently before any deliberation begins?

At that point, telling someone to ‘think critically’ is like asking them to optimise a system they cannot see, using criteria they do not recognise. The instruction is not offensive. It’s unintelligible. This is why so many contemporary disputes feel immune to argument. Not merely heated, but strangely orthogonal. You aren’t rebutted so much as translated into something else entirely: naïve, immoral, dangerous, unserious. And you do the same in return.

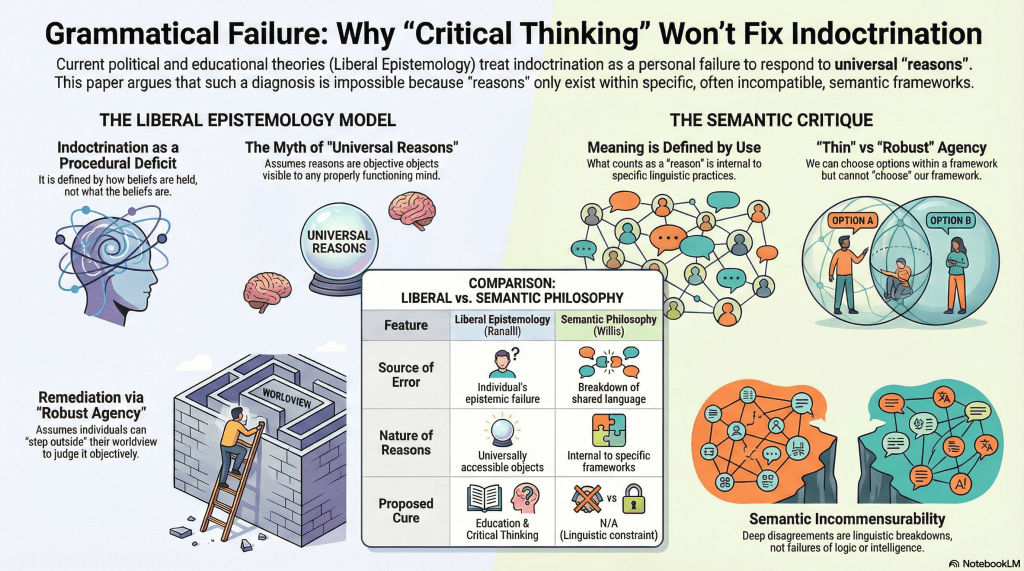

Liberal epistemology has a neat explanation for this. It treats these failures as agent-level defects: insufficient openness, motivated reasoning, epistemic irresponsibility. The problem is always how people reason. The argument of Grammatical Failure is that this diagnosis is systematically misplaced. The real constraint, in many cases, lies upstream of reasoning itself. It lies in the semantic frameworks that determine what can count as a reason in the first place. When those frameworks diverge, deliberation doesn’t fail heroically. It fails grammatically.

This doesn’t mean people lack agency. It means agency operates within a grammar, not over it. We choose, revise, and reflect inside spaces of intelligibility we did not author. Asking deliberation to rewrite its own conditions is like asking a sentence to revise its own syntax mid-utterance. The result is a familiar pathology. Disagreement across frameworks is redescribed as epistemic vice. Category rejection is mistaken for weak endorsement. Indoctrination becomes a label we apply whenever persuasion fails. Not because anyone is lying, but because our diagnostic tools cannot represent what they are encountering.

The paper itself is not a manifesto or a programme. It doesn’t tell you what to believe, how to educate, or which politics to adopt. It does something more modest and more uncomfortable. It draws a boundary around what liberal epistemology can coherently explain – and shows what happens when that boundary is ignored.

Sometimes the problem isn’t that people won’t think.

It’s that they are already thinking in a grammar that your advice cannot reach.