Picture this: you’re strolling along the beach, admiring the marine life in the rock pools. You spot a starfish, a jellyfish, and a seahorse. Pop quiz: which of these creatures is actually classified as a fish?

- Starfish

- Jellyfish

- Seahorse

- Banana

If you answered “seahorse”, congratulations! You’ve just dipped your toe into the wonderfully weird world of marine biology and linguistic evolution. But don’t pat yourself on the back just yet, because we’re about to dive deeper into this ocean of confusion.

But something is fishy in Denmark. You see, in the grand aquarium of the English language, not all that glitters is fish, and not all fish sparkle. Our ancestors, bless their linguistically challenged hearts, had a rather broad definition of what constituted a ‘fish’. Anything that lived exclusively in water? Chuck it in the ‘fish’ bucket!

Your medieval five-a-day fruit and veg platter?

All meat, baby!

But wait, there’s more! While they were happily labelling every aquatic creature as ‘fish’, they were also using the word ‘meat’ to describe, well, pretty much anything edible. That’s right—your medieval five-a-day fruit and veg platter? All meat, baby!

So, how did we go from this linguistic free-for-all to our current, more discerning categorisations? And why do we still use terms like ‘starfish’ and ‘jellyfish’ when they’re about as fishy as a beef Wellington?

Strap on your scuba gear, dear reader. We’re about to take a deep dive into the murky waters of etymology, where we’ll encounter some fishy facts, meaty morsels of linguistic history, and maybe—just maybe—learn why a seahorse is more closely related to a cod than a sea cucumber is to a cucumber.

Welcome to our tale of linguistic evolution. It’s going to be a whale of a time! In this linguistic deep dive, we’ll explore the meaty truth about ‘mete’, fish out the facts about ‘fisc’, and navigate the choppy waters of modern usage.

The Meaty Truth: When Apples Were Meat

Imagine, if you will, a world where asking for a meat platter at your local deli might result in a fruit basket. No, this isn’t a vegetarian’s fever dream—it’s actually a peek into the linguistic past of our ancestors.

In Old English, the word ‘mete’ (IPA /’mit ə/, and not to be confused with the modern verb ‘to meet’) was a catch-all term for food. Any food. All food. If you could eat it, it was ‘mete’. Your apple? Mete. Your bread? Mete. That leg of lamb? Also mete, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

This broad definition persisted for centuries. Chaucer, in his 14th-century work “The Canterbury Tales”, wrote of “a Cok, hight Chauntecleer” (a rooster named Chauntecleer) who “For his brenning lay by Pertelote” (a hen). Yes, you read that right. Chickens were laying eggs; Chaucer was writing about “food” and “birds”; and somewhere, a medieval nutritionist was having an existential crisis.

But language, like a slowly simmering stew, changes over time. By the 14th century, ‘mete’ had started to narrow its focus, increasingly referring to the flesh of animals. It’s as if the word itself decided to go on a protein-heavy diet.

By the 18th century, ‘meat’ (having picked up its modern spelling along the way) had pretty much settled into its current meaning: the flesh of animals used as food. Though remnants of its broader past linger in more places than you might expect:

- Phrases like “meat and drink” still mean food and beverages in general.

- The term “nutmeat” refers to the edible part of a nut.

- Fruits and vegetables can have “meaty” parts – we’re looking at you, avocados and tomatoes!

- “Sweetmeat” doesn’t involve meat at all, but refers to candies or sweets.

So, the next time you’re describing the succulent flesh of a ripe peach as “meaty”, know that you’re not being weird – you’re being etymologically nostalgic. And when someone tells you to “meat and greet“, don’t bring a steak to the party. Unless, of course, it’s that kind of party. In which case, maybe bring enough to share?

This culinary journey through time just goes to show that when it comes to language, the proof is in the pudding. And yes, once upon a time, that pudding would have been called ‘meat’ too! Now that we’ve carved up the history of ‘meat’, let’s cast our net into the world of ‘fish’.

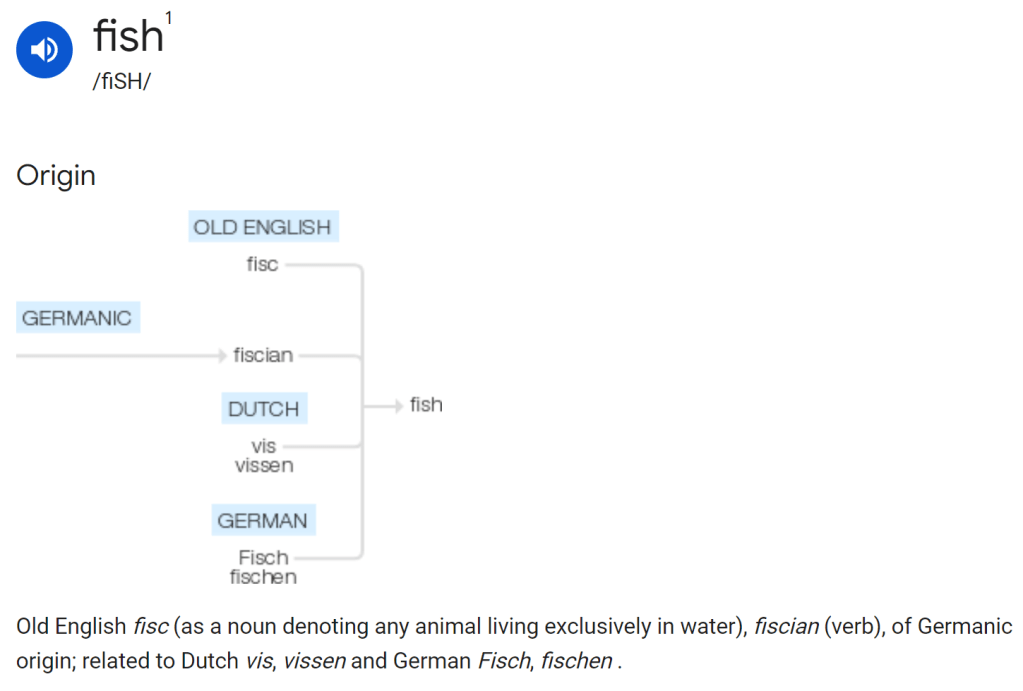

Something’s Fishy: Casting a Wide Net

From land to sea, our linguistic journey now dives into deeper waters to explore the slippery history of the word ‘fish’. Prepare to have your gills blown, because this tale is more twisted than an octopus playing Twister.

In Old English, our linguistic ancestors used the word ‘fisc’ (IPA /fɪsk/) to refer to, well, pretty much anything that called water its home. If it swam, floated, or generally looked bewildered in an aquatic environment, it was a ‘fisc’.

This cast-iron skillet approach to classification meant that whales, seals, and even crocodiles were all lumped into the ‘fisc’ category. It’s as if our forebears took one look at the ocean, threw up their hands, and said, “Eh, it’s all fish to me!”

This broad definition persisted for centuries, leading to some rather fishy nomenclature that we’re still untangling today:

- Jellyfish: Despite their name, these gelatinous creatures are about as far from fish as you are from your second cousin twice removed on your mother’s side.

- Starfish: These spiny echinoderms are more closely related to sea urchins than to any fish. They’re the marine equivalent of finding out your cat is actually a very convincing raccoon.

- Cuttlefish: These crafty cephalopods are molluscs, more akin to octopuses and squids than to any fish. They’re the masters of aquatic disguise, fooling both prey and etymologists alike.

- Shellfish: This term covers a motley crew of crustaceans and molluscs. Calling a lobster a fish is like calling a butterfly a bird – poetic, perhaps, but scientifically fishy.

As scientific understanding grew, the definition of ‘fish’ narrowed. By the 16th century, scholars were beginning to distinguish between ‘fish’ and other aquatic animals. However, the old, broad use of ‘fish’ had already left its mark on our language, like a stubborn fish smell that lingers long after the seafood dinner is over.

Today, in biological terms, ‘fish’ refers to gill-bearing aquatic animals lacking limbs with digits. But in culinary and cultural contexts, the term is still often used more broadly. So next time you’re at a seafood restaurant pondering whether to order the fish or the shellfish, remember: it’s all ‘fisc’ to your linguistic ancestors!

The Great Divide: Fish or Not Fish?

Now that we’ve muddied the waters thoroughly, let’s try to separate our fish from our not-fish. It’s time for the ultimate marine showdown: “Fish or Not Fish: Underwater Edition”! Let’s swim through some specific examples that highlight this fishy classification conundrum.

Starfish: The Stellar Impostor

Despite their fishy moniker, starfish are about as much fish as a sea star is an actual star. These echinoderms are more closely related to sea urchins and sand dollars than to any fish. With their five-armed symmetry and lack of gills or fins, starfish are the marine world’s ultimate catfish (pun intended).

Jellyfish: The Gelatinous Pretender

Jellyfish might float like a fish and sting like a… well, jellyfish, but they’re no more fish than a bowl of jelly. These cnidarians lack bones, brains, and hearts, making them more like drifting water balloons than actual fish. They’ve been pulling off this aquatic masquerade for over 500 million years!

Cuttlefish: The Crafty Cephalopod

Don’t let the name fool you – cuttlefish are cephalopods, more closely related to octopuses and squids than to any fish. These masters of disguise can change their appearance rapidly, making them the chameleons of the sea. They’re the ultimate marine conmen, fooling both prey and etymologists alike.

Shellfish: The Armoured Anomalies

‘Shellfish’ is a catch-all term for a motley crew of crustaceans and molluscs. Calling a lobster or an oyster a fish is like calling a butterfly a bird – it might fly, but that doesn’t make it right. These hard-shelled creatures are about as far from fish as you can get while still living in water.

Seahorses: The Fishy Exception

Plot twist! Despite their equine appearance, seahorses are indeed true fish. These peculiar creatures belong to the genus Hippocampus (which literally means “horse sea monster” in Greek). Here are some fin-tastic facts about our curly-tailed friends:

- Male Pregnancy: In a twist that would make seahorse soap operas very interesting, it’s the male seahorses that get pregnant and give birth.

- Monogamy: Unlike many fish, seahorses are monogamous. They perform daily greeting rituals to reinforce their pair bonds. It’s like underwater ballroom dancing but with more fins.

- Camouflage: Seahorses are masters of disguise, able to change colour to blend in with their surroundings. They’re the underwater equivalent of a charismatic chameleon.

- Snouts: Their tubular snouts work like built-in straws, perfect for sucking up tiny crustaceans. It’s nature’s version of a Capri Sun.

So there you have it – a horse that’s a fish, and a bunch of “fish” that aren’t. If this doesn’t highlight the delightful absurdity of language evolution, I don’t know what will!

Modern Usage and Misconceptions: A Kettle of Fish

Now that we’ve unravelled this tangled net of fishy nomenclature, let’s surface and see how these linguistic oddities persist in modern times. It’s a veritable school of misconceptions out there! Just as our ancestors broadly applied ‘mete’ and ‘fisc’, we continue to cast a wide net with our fishy terms today.

The Persistent “Fish”

Despite our best scientific efforts, many misnomers stubbornly cling to our language like barnacles to a ship’s hull:

- Silverfish: These squirmy household pests are neither silver nor fish. They’re insects that have been sneaking into our bathtubs and bookshelves for over 400 million years, laughing at our misguided naming conventions.

- Crayfish: Also known as crawfish or crawdads, these freshwater crustaceans are more closely related to lobsters than to any fish. They’re the inland cousins who couldn’t afford beachfront property.

- Fishfingers: A childhood staple that contains fish but isn’t fingers. Unless you know something about fish anatomy that we don’t…

The Culinary Conundrum

In the world of cuisine, the line between ‘fish’ and ‘seafood’ is blurrier than a fish’s vision out of water:

- Many menus separate ‘fish’ from ‘seafood’, with the latter often including shellfish and sometimes even seaweed. It’s as if the ocean decided to categorise its inhabitants based on their starring roles in Disney movies.

- The phrase “fish and chips” stubbornly refuses to become “seafood and chips”, even when the dish includes non-fish like calamari. It’s a linguistic tradition as crispy and golden as the batter itself.

The Vegetarian’s Dilemma

Pity the poor vegetarians navigating this linguistic minefield:

- Some vegetarians eat fish but not meat, leading to the term “pescatarian”. It’s as if fish decided to identify as vegetables just to complicate matters.

- The question “Do you eat fish?” is often asked separately from “Are you vegetarian?”, as if fish were secretly plants with fins.

The Final Catch

In the end, language is a living, breathing entity that evolves faster than you can say “coelacanth” (which, by the way, is a fish that was thought to be extinct until it wasn’t – talk about a plot twist!).

While scientists may pull their hair out over our continued misuse of ‘fish’, the rest of us can simply enjoy the rich tapestry of language these terms have woven. After all, in the grand aquarium of English, it’s the linguistic oddities that make the view so interesting.

In the world of language, sometimes it’s okay to let sleeping dogfish lie.

So the next time you find yourself in a debate about whether a starfish is a fish, or why we call it shellfish when there’s no fish involved, remember: in the world of language, sometimes it’s okay to let sleeping dogfish lie.

Conclusion: So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish!

As we surface from our deep dive into the murky waters of etymology, we find ourselves with a tackle box full of linguistic curiosities. We’ve navigated the broad seas of ‘mete’, trawled through the expanding net of ‘fisc’, and somehow ended up in a world where seahorses are fish, but starfish aren’t.

Language, much like the ocean, is vast, mysterious, and full of surprises.

Our journey has shown us that language, much like the ocean, is vast, mysterious, and full of surprises. It evolves and changes, sometimes leaving behind fascinating fossils in our everyday speech. These linguistic relics remind us of a time when our ancestors looked at the sea and decided that anything wet and wriggly qualified as a fish.

From the “meaty” part of a fruit to the fish fingers in your freezer, from the crayfish in streams to the silverfish in your bathroom, these terms continue to swim through our language, blissfully unaware of their misclassification. They’re like linguistic dolphins, playfully leaping through our conversations, occasionally confusing vegetarians and marine biologists alike.

And here’s a thought to chew on: given what we’ve learned about the evolution of the word ‘meat’, could this linguistic journey have unintended consequences in other areas? For instance, when Catholics abstain from ‘meat’ on Fridays, are they following the modern interpretation of the word, or its original, broader meaning of ‘food’? It’s a question that would require diving into early Greek, Aramaic, and Latin texts to explore fully. But it just goes to show how the ripples of language evolution can reach far beyond our dinner plates and into the very core of cultural and religious practices.

So the next time you find yourself pondering whether that seafood platter is really all ‘fish’, or why we still call it the “fruit of the sea” when we know better, remember this tale. Embrace the delightful absurdity of language evolution. After all, in the grand ocean of communication, it’s these quirks and idiosyncrasies that make our linguistic journey so fascinating.

And if all else fails, just smile enigmatically and say, “So long, and thanks for all the fish!” Who knows? You might just be speaking to a dolphin disguised as a human, trying to warn you about the impending destruction of Earth to make way for a hyperspace bypass. But that, dear readers, is a whole other kettle of fish… or should we say, a different cut of meat?