Welcome to Part 2 of a Week-Long Series on the Evolution and Limits of Language!

This article is part of a seven-day exploration into the fascinating and often flawed history of language – from its primitive roots to its tangled web of abstraction, miscommunication, and modern chaos. Each day, we uncover new layers of how language shapes (and fails to shape) our understanding of the world.

If you haven’t yet, be sure to check out the other posts in this series for a full deep dive into why words are both our greatest tool and our biggest obstacle. Follow the journey from ‘flamey thing hot’ to the whirlwind of social media and beyond!

Saussure and the Signified: Words as Slippery Symbols

Fast-forward a few thousand years, and humans are no longer just warning each other about hot flames or toothy predators. We’ve moved on to the exciting world of abstract thought, but the language tools we’re using haven’t quite caught up. Enter Ferdinand de Saussure, who basically waltzed in to tell us, ‘Hey, all those words you’re throwing around? They’re not doing what you think they’re doing.’

Saussure gave us the idea of the signifier and the signified. Now, don’t let the fancy terms fool you. It’s just a way of pointing out that when we say ‘tree’, we’re not actually talking about a tree. No, we’re using the word ‘tree’ as a symbol – a signifier – that points to the idea of a tree. The signified is the actual concept of ‘tree-ness’ floating around in your brain. But here’s the kicker: everyone’s idea of a tree is a little different.

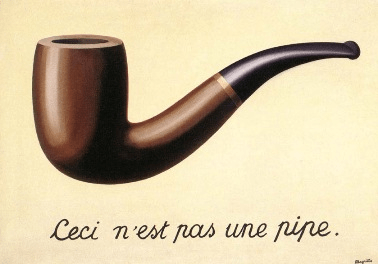

And this isn’t just a language problem – it’s an art problem too. Enter René Magritte, the surrealist artist who really drove this point home with his famous painting, Ceci n’est pas une pipe (‘This is not a pipe’). At first glance, it looks like a straightforward picture of a pipe, but Magritte was making a deeper point. It’s not actually a pipe – it’s an image of a pipe, a representation. You can’t stuff it with tobacco and smoke it, because what you’re looking at is a representation, not the real thing.

In the same way, when we use words, we’re not talking about the thing itself – we’re just waving a flag toward the concept of that thing. So, when you say ‘tree’, you’re really saying ceci n’est pas un arbre – this is not a tree. It’s just a word, a placeholder, a verbal painting of something real. And just like Magritte’s pipe, it’s easy to get confused. You might think you’re talking about the same tree, or the same ‘freedom’, but all you’ve got is a symbol – and everyone’s symbol looks a little different.

This is where things start to unravel. Words are slippery symbols, and as soon as we move away from concrete, physical objects – like trees or, yes, pipes – and into abstract ideas, like ‘justice’ or ‘truth’, the symbols become even harder to hold onto. The cracks in language start to widen, and before you know it, you’re no longer even sure if you’re talking about the same concept at all.

Language, Saussure argues, isn’t this neat, objective system we thought it was. It’s a game we’re playing, and the rules are written in invisible ink. By the time we get to abstract nouns, we’re basically playing with loaded dice. You think you’re communicating clearly, but every word you use is just a placeholder for the idea you hope the other person has in their head. And nine times out of ten? They don’t.

So, while early humans were struggling to agree on the ‘flamey thing’, we’re here trying to agree on concepts that are infinitely more complicated. And Saussure? He’s just sitting in the corner with a smirk, telling us we never had control over language in the first place. “Good luck with your ‘truth'”, he seems to be saying. ‘I’m sure it’ll mean the same thing to everyone’.

Abstraction: Enter Freedom, Truth, and Confusion

Now that we’ve wrapped our heads around the fact that words are nothing but slippery symbols, let’s take it up a notch. You thought ‘tree’ was tricky? Try something more abstract. Enter: freedom, truth, justice. Things that can’t be seen, touched, or stuffed into a pipe. Here’s where language goes from being slippery to downright treacherous.

See, early language worked because it was tied to concrete things. ‘Toothey thing scary’ wasn’t up for debate. Either you got eaten, or you didn’t. Simple. But then humans, ever the overachievers, decided it wasn’t enough to just label the world around them. They wanted to label ideas, too – things that don’t have any physical form but somehow drive us all crazy.

Take ‘freedom’, for instance. Sounds nice, right? Except, if you ask ten people what it means, you’ll get ten different answers. For some, it’s ‘freedom from’ something – a kind of liberation. For others, it’s ‘freedom to’ do whatever you want, whenever you want. And yet for others, it’s an abstract ideal tied up in political philosophy. Suddenly, you’re not just dealing with different trees – you’re dealing with entirely different forests.

The same goes for truth. Is it objective? Subjective? Relative? Absolute? Everyone’s got a different take. Plato had his own grand ideas about ‘Truth’ with a capital T, while Nietzsche basically rolled his eyes and said, ‘Good luck with that’. You’re out here using the word, assuming it means the same thing to everyone else, but really you’re all just talking past each other.

And don’t even get started on justice. Some say it’s about fairness, others say it’s about the law, and still others think it’s just a nice idea for dinner party debates. The problem with these words – these abstract nouns – is that they represent ideas that live entirely in our heads. Unlike the ‘flamey thing’ or the ‘toothey thing’, there’s no physical reality to pin them to. There’s no universally agreed-upon image of ‘freedom’ that we can all point to and nod along, like Magritte’s pipe. There’s just… vague agreement. Sometimes. On a good day.

This is where language really starts to break down. You might think you’re having a productive conversation about ‘freedom’ or ‘truth’, but half the time, you’re speaking different languages without even realising it. Words like these aren’t just slippery – they’re shapeshifters. They bend and morph depending on who’s using them, when, and why.

So, while early humans were busy with their simple, effective ‘toothey thing scary’, we’re now trying to nail down ideas that refuse to be nailed down. What started as a useful survival tool has turned into a game of philosophical Twister, with everyone tied up in knots trying to define something they can’t even see. And, as usual, language is just standing in the corner, smirking, knowing full well it’s not up to the task.

2 thoughts on “From Signs to Abstractions: The Slippery Slope of Meaning”